The History of Judges Hill

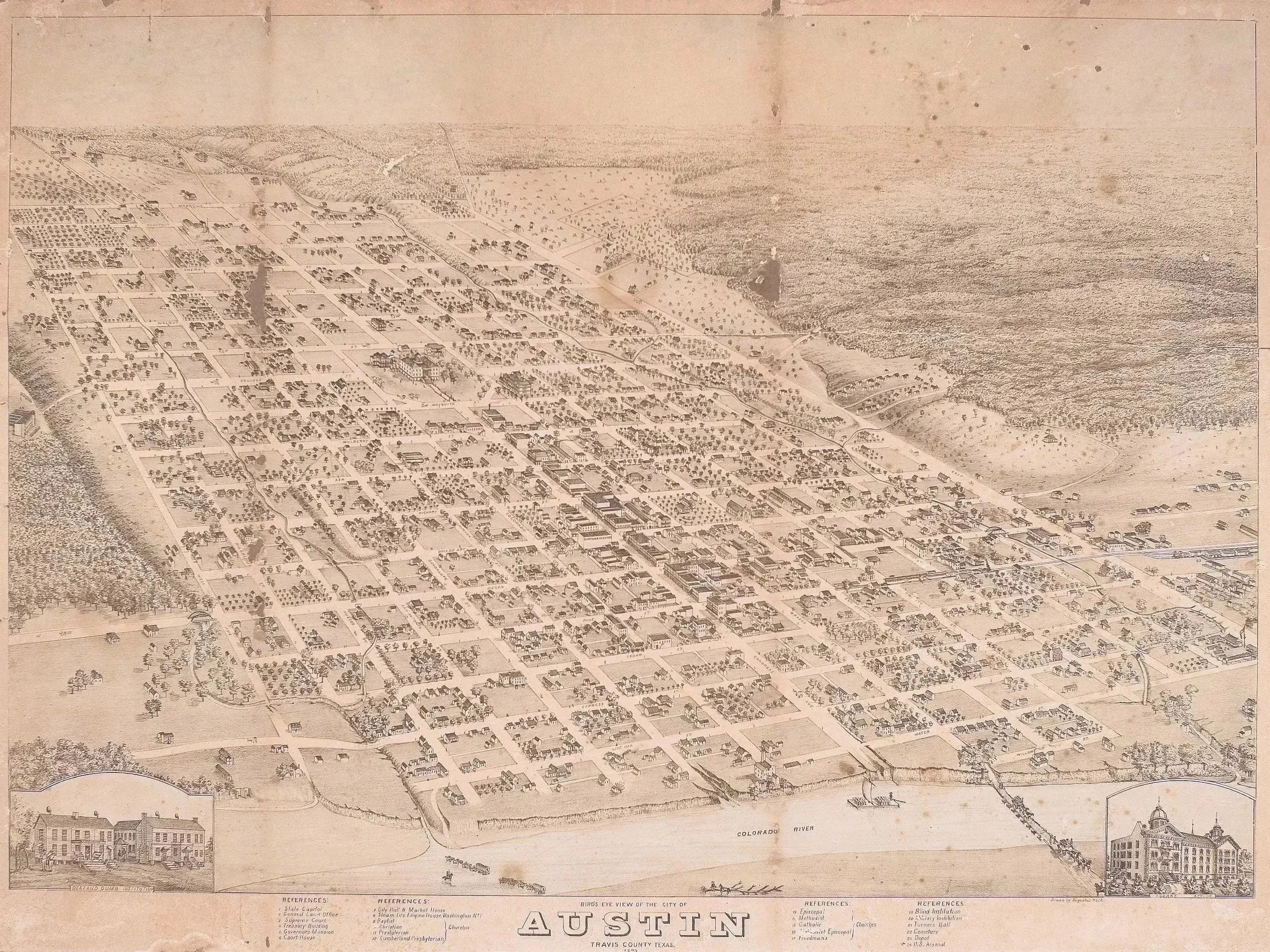

Long before it was surrounded by the fourth-largest Texas metro area, the area now known as Judges Hill was a literal wilderness. Shoal Creek marked Austin’s original western boundary when the city was laid out in 1839. Long before that, Native American tribes used the area for hunting and gathering, taking advantage of the creek’s access to both hills and plains. The Tonkawa were the primary pre-European inhabitants, with Lipan Apaches, Wacos, and later Comanches also using Shoal Creek as a travel route. Evidence of this deep history remains today through burial mounds and flint arrowheads found along the creek’s banks. When Edwin Waller platted the city in 1839, this land was designated as “outlots” on the far western edge of the new capital, a rugged landscape bordering Shoal Creek that was still subject to raids by indigenous tribes.

Its transformation began in 1851 when Colonel Elijah Sterling Clack Robertson built the first known home on a bluff overlooking the creek. Soon, the area’s proximity to the State Capitol and City of Austin courthouse began attracting the city’s most prominent attorneys and judges, giving the neighborhood its enduring name, Judges Hill.

Formative Years of Judges Hill: The Victorian Era

c. 1851-1900

The oldest surviving home from this pioneer era is the magnificent Greek Revival mansion at 1703 West Avenue, known as “Westhill.” Attributed to master builder Abner Cook (who also built the Texas Governor's Mansion), this stately home was constructed in 1855 and set the tone for the neighborhood as a secluded haven for Austin’s influential citizens. For years, development was sparse, with a few large homesteads and country-style estates defining the landscape. Behind some of these grand homes, such as Robertson’s, were log cabins that housed the enslaved men and women whose labor helped build these early homesteads.

The arrival of the Houston and Texas Central Railway in 1871 marked a significant change. The railroad solidified Austin’s status as a trading hub and brought an influx of new wealth, entrepreneurs, and influential figures. Almost overnight, Judges Hill became one of the most desirable places to live. The large, original outlots were carved into smaller parcels to meet the demand, and the neighborhood experienced a construction boom that lasted for the rest of the century.

This period of prosperity gave the neighborhood its signature Victorian character. Grand, ornate homes in the latest architectural fashions began to line West Avenue and Rio Grande Street. Styles ranged from the asymmetrical elegance of the Queen Anne style, like the 1895 Ruggles-Smith House with its distinctive turret. These elaborate homes, with their decorative trim and complex rooflines, announced the arrival of a new, wealthy class and established Judges Hill as Austin's most fashionable address.

The Chandler-Shelley House, also known as “Westhill,” is located at 1703 West Avenue. A Greek Revival likely built by Abner Cook around the same time, circa 1855, he was building the nearby Texas Governor’s Mansion.

The Early 20th Century Revival Phase

c. 1900-1945

As the 20th century dawned, the nation’s—and Judges Hill’s—architectural tastes began to shift. Inspired by the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a renewed interest in classical design swept the country. The result in Judges Hill was the construction of some of Austin's most lavish Neoclassical homes. Featuring monumental columns and grand, stately facades, houses like the William T. Caswell House (1904) and the spectacular Goodall Wooten House (1900) became the new symbols of wealth and status for the neighborhood’s powerful residents.

At the same time, a new wave of “American” architecture began to fill in the neighborhood's remaining lots, reflecting a growing middle class. From high-style, architect-designed homes to more modest bungalows lining entire streets, the Craftsman style was wildly popular from about 1909 through the 1920s. This new layer of development, further spurred by the arrival of an electric streetcar line on Rio Grande Street, created a denser and more diverse neighborhood fabric.

After World War I, soldiers returning from Europe brought with them an appreciation for historic European architecture, sparking a trend of “Period Revival” styles. From the 1920s through the 1930s, new homes were built in romantic styles such as Tudor Revival, Italian Renaissance, and Spanish Revival. This era also saw the first significant institutional encroachment into the residential enclave with the construction of the original St. David’s Hospital on West 17th Street in 1928.

The Great Depression brought change and exposed a growing divide within the neighborhood. In the 1930s, the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps that rated mortgage risk. It graded the western side of Judges Hill, with its large, single-family estates, as “A – Best.” However, the eastern section, with its smaller lots, duplexes, and proximity to commercial streets, was rated “C – Definitely declining.” This official designation reinforced a division in the neighborhood that would influence its development for decades to come.

[Top] The Goodall Wooten Mansion at 1900 Rio Grande. Built 1898-1900.

[Bottom] Exterior of the St. David's Hospital building at 606 W. 17th. The building is now the Rio House Apartments.

The Postwar Boom & The Pressure of Progress

c. 1946-Present

Following World War II, Austin experienced a massive boom. The tastes of returning GIs and their young families shifted away from romantic revivals and toward modern efficiency. The long, low-slung Ranch house became the most popular style in the nation, and many were built as infill in Judges Hill. For the more adventurous, sleek Contemporary and Mid-Century Modern homes appeared, such as the architect-designed Granger House (1952) and the Matsen House (1953). This era also saw the platting of the neighborhood’s first formal subdivision in 1947, Vance Park, carved from the final remaining estate of Miss Julia Vance.

By the 1960s, the pressures of a growing city began to close in. The expansion of the nearby University of Texas and the state government created an insatiable demand for housing. The neighborhood’s demographics shifted younger as large single-family homes were demolished to make way for multi-family housing. New, modern apartment complexes, such as the 50-unit Miss Texas Apartments built for female students in 1962, rose on lots that once held Victorian mansions.

This trend of redevelopment has continued to the present day. The eastern half of the district, in particular, has seen significant change, with historic homes being replaced by office buildings, restaurants, and parking garages. Many of the grand residences that survived have been converted from single-family homes into commercial offices.

Judges Hill remains a remarkable historical treasure with streets that tell the story of Austin’s evolution, from a rugged frontier outpost to a bustling modern city. Due to its remarkable array of architecture and its rich historical roots, the neighborhood is now recognized as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The proposed Judges Hill Historic District is a unique locality where stately 19th-century mansions, charming Craftsman bungalows, and sleek Mid-Century Modern homes stand side-by-side, a living museum of the city’s rich and complex past.

The history of Judges Hill has been compiled and is largely contributed to by Phoebe Allen, The City of Austin in consultation with Emily Payne and the HHM Team, and Terri Meyers.

The Granger House was built in 1952 by Architect Charles Granger.

Video courtesy of Preservation Austin & Phoebe Allen.